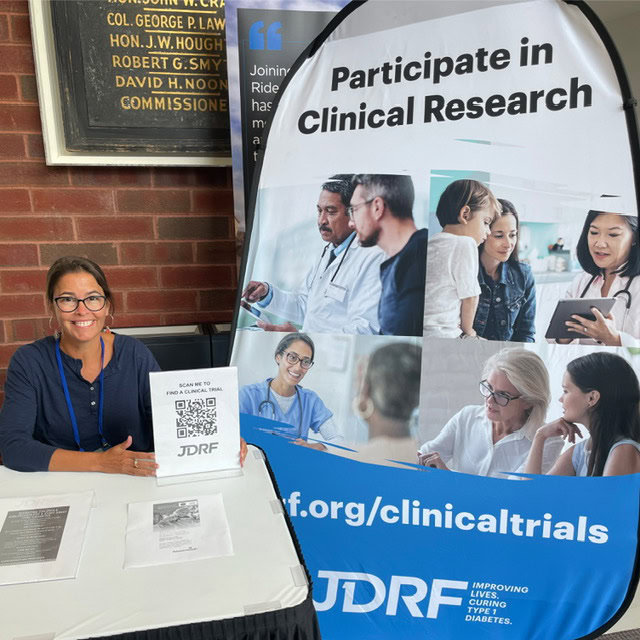

This article was written by Alecia Wesner (pictured above, right), a Participant Advisory Council (PAC) member, a Clinical Trial Education Volunteer, and long-time Breakthrough T1D supporter. Alecia’s story details her lived experiences with type 1 diabetes, participation in clinical trials, and her journey to joining the PAC. The views expressed by the author are her own and are not necessarily representative of Breakthrough T1D or our leadership, employees, or supporters.

Where it all began

I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in 1979 in suburban Philadelphia. I had just finished kindergarten, learned to ride a bike, and spent summer days pedaling the block. I was thirsty all the time. I was a new little cyclist and it was summer, of course I was thirsty! One day I drank an entire quart of iced tea, within mere minutes, at a neighbor’s house. That was the red flag. My pediatrician sent us to the local hospital, and multiple nurses and a doctor held me down as they repeatedly struggled to find a vein for a blood draw. My Dad took me for pancakes afterwards—definitely not ideal without insulin. Later, there was a phone call and my Dad left the house. I saw him sitting outside with his head in his hands. It was the first time I saw him cry. My Mom pulled me away from the window.

I spent the next week and a half in a children’s ward of a Philadelphia hospital. My parents were trained to care for me, and I practiced giving insulin shots on an orange while arts and crafts kept me busy. I spoke to my parents every night on a pay phone, whispering, while crying that I wanted to come home. My parents would say the other children in the ward needed me to be brave. This was long before continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) or even portable blood glucose meters. My parents learned to check my glucose by testing my urine with chemicals in test tubes, a non-exact way to measure glucose range. When I came home, neighbors were anxious because many believed diabetes was contagious.

A designer’s perspective on T1D clinical trials

Clinical trials and research have been central to my life. Clinical trials are essential to proving a concept, where ideas are tested rigorously and then refined.

My training as an industrial designer has always been about the intersection of people and systems. Whether designing a lighting fixture, a user interface, or an educational program, I think first about human needs, usability, and empathy.

That design lens informs how I view research. A study protocol is not just a list of procedures. It is a system that has users, interfaces, and outcomes. Participants are the users. Devices and consent forms are the interfaces. The data is the outcome. When design thinking is applied to research, studies become more accessible, clearer, and better aligned with the realities of daily life.

A defining experience

For those of us living with type 1 diabetes, research is not just academic—it is the path to a better quality of life. I have participated in nine clinical trials and numerous studies. I tested early automated insulin delivery (AID) systems over many years, assessing software and hardware which led to commercially available AID systems. I tested an implantable continuous glucose monitor, and I took part in studies that examined complications and diabetes biomarkers. Each trial taught me about technology, the human body (specifically mine), and how research truly impacts lives.

The experience that defined my clinical trial pathway was in my mid-20’s. I developed retinopathy. Due to a great macular specialist, I received aggressive laser treatments for years. It was scary, especially as a young professional starting a career in product development and visual design. The treatments that preserved my vision were possible because others had volunteered for research for years, even decades, before me. That reality gave me enormous gratitude, and it also gave me a sense of responsibility. Participating in research is how I have been able to embrace a life philosophy of “Do good, feel good” and ultimately pay it forward. Clinical trials and research studies are how we learn and design better solutions for everyone who follows.

Joining the Participant Advisory Council

My designer’s perspective led me to join the Breakthrough T1D Participant Advisory Council (PAC). I had been involved with Breakthrough T1D for many years as a Clinical Trial Education Volunteer, an advocate, and former board member. The PAC offered a new opportunity to bring lived experience directly into the research process.

On the council, we review trial designs, advise on participant burden, critique consent language, and recommend practical changes in the hope of lowering barriers to participation. My concern initially was that I’d be a token voice, but we are not. We are advisors who help researchers see the experience through the eyes of the people who will take part in the studies—people who may ultimately benefit from the data gained.

One of the most meaningful ways I contributed as a PAC member was in June 2025, when I spoke on a panel about disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) at the American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions in Chicago. The panel focused on disease-modifying therapies designed to preserve C-peptide (a biomarker for insulin production) and slow or stop the progression of T1D. I represented the lived experience, and I brought the perspective of a long-term clinical trial participant and an educator who helps others understand and navigate research opportunities.

Using my voice to spread awareness about clinical trials

There were numerous questions to be addressed. One question asked how patients view trials targeted at specific subsets of the T1D population compared to all open trials. My answer was that subsets are still part of the whole community, and a win in one group can expand to broader benefits. At the same time, being excluded from any study can feel deeply personal. People who have made the decision to participate and then hear they do not qualify may feel a sense of loss and frustration. That is where clear communication and education matter. Explaining why inclusion and exclusion criteria exist, offering information about other potential trials, and keeping lines of communication open helps people stay engaged rather than feeling shut out.

Recruitment, especially for new onset trials, is another challenge the panel addressed. Speed matters because opportunities for early intervention are time-sensitive. Effective recruitment requires a network approach. Endocrinologists and clinicians are critical, but so are community organizations, advocacy groups, and peer networks. Many newly diagnosed people search for help and connect with the T1D community to find resources. When trusted peers share information about trials, it not only demystifies the process and reduces the emotional burden for families facing a new diagnosis—it opens doors.

We also discussed patient-relevant endpoints in DMT trials. Clinical metrics matter, but they do not capture everything people live with. Participants prioritize outcomes that reduce daily burden, delay disease progression, improve long-term health, lower the risk of severe hypoglycemia, preserve endogenous insulin, enhance glycemic control, potentially reduce lifetime treatment costs, and sustain hope. These are the practical changes that matter in everyday life.

Education and implementation were the final themes I emphasized. Clinicians and patients alike need clear information about DMTs and about how early interventions would be implemented in real-world settings. Linking DMTs to screening efforts ensures that people in the early stages of T1D are identified and connected with options. Volunteers, advocacy groups, and community programs are essential for amplifying success stories and helping clinicians and patients understand how to access emerging therapies.

“Research is deeply personal”

All of this ties back to design. When we include lived experience in research design, the results are more humane, relevant, and practical. We reduce friction that prevents people from participating, and we improve outcomes by focusing on the needs of real users. My perspective as both a person who lives with T1D and an industrial designer helps me see where small design decisions have large effects.

Looking forward, I remain committed to this work because research is deeply personal. It saved my vision. It offers better tools and brighter possibilities. It is also a way to honor those who volunteered before me and to give others the chance to benefit. Whether I am advising on study protocols, speaking on national panels, or teaching people how to find trials, I see it as part of the same lifelong commitment: to make life with T1D easier, to improve the design of treatments and systems, and to help guide us toward the ultimate goal: cures.

If you or someone you know may be interested in joining the Participant Advisory Council, please reach out to Michelle Simes-Kennedy at MSimes-Kennedy@BreakthroughT1D.org.

Learn more about clinical trials

Visit Breakthrough T1D’s clinical trials web page to learn more about how you can get involved in clinical trials. Use our clinical trial matching tool to find recruiting trials near you that you may be eligible for. Connect with a Clinical Trial Education Volunteer in your area to better understand the process and get your questions answered.