What is the pipeline?

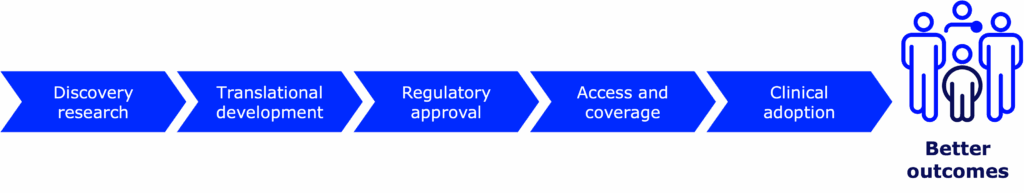

Every new medical device, therapy, treatment, and drug—including those for type 1 diabetes (T1D)—goes through the drug development pipeline. Getting a new therapy or device from the earliest stages of research eventually into the hands of people with T1D is a complicated process. Science takes time (from years to decades!), money (from hundreds of millions to billions!), and brainpower (lots and lots of brilliant scientists, doctors, researchers, and more)—and lots of it.

That’s what drives us and our work in the pipeline: people with T1D doing better.

This process is complex, to say the least. There are safety checks at every step of the way. Data are scrutinized, and preclinical and clinical testing must meet ethical standards. In fact, many new drugs and devices don’t make it very far in the pipeline—and those that do take a long time to get there.

Breakthrough T1D is unique in that we work across the entire pipeline—from start to finish—for every promising therapy or device that we invest in. Between Research, Advocacy, and Medical Affairs, we work at every single step to accelerate progress and get new treatments to people with T1D faster than ever.

That’s our value proposition. That’s what makes supporting us different than supporting an individual researcher, or a university, or a company.

Let’s dive a little deeper into the pipeline—and how we’re turbocharging it.

Time and money

Total money spent in the diabetes space in FY24:

$146 million

By Breakthrough T1D

$521 million

Total T1D research support, including by Breakthrough T1D

$160 million

By the Special Diabetes Program

$412.9 billion

In healthcare

Total investments in new drugs and devices:

12 to 15 years

Estimated time it takes a new drug to get to the clinic

$1 billion

Estimated total cost to bring a new drug from discovery research to the clinic

3 to 7 years

Estimated time it takes a new medical device to get to the clinic

$522 million

Estimated total cost to bring a new medical device from discovery research to the clinic

The pipeline in action: Automated insulin delivery systems

Automated insulin delivery systems vs. artificial pancreas systems

At the very beginning, these devices were called artificial pancreas (AP) systems. Today, they are called automated insulin delivery (AID) systems. We’ll be referring to them as AID systems going forward.

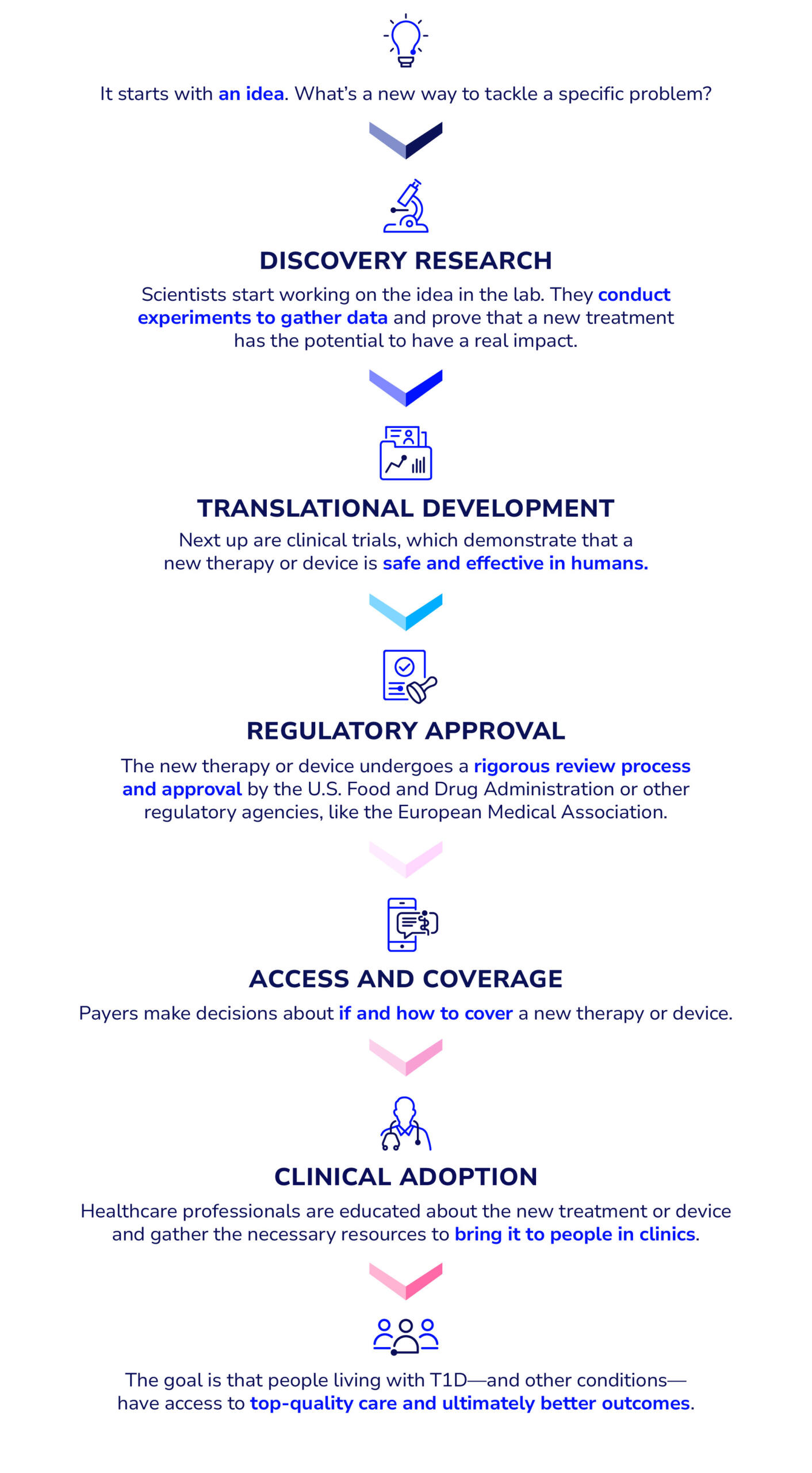

The process at a glance:

$171 million

The amount of money Breakthrough T1D spent on AID system-related research from 2005 to 2024

12 years

The amount of time it took for next-generation AID systems to go from discovery research to clinical adoption after Breakthrough T1D became involved

Hundreds of millions of dollars

Total investment in AID systems from all stakeholders

60+ years

The amount of time it took for AID systems to become a reality, starting with the first experimental AP system in 1964

A deeper dive into the process:

Breakthrough T1D x AID systems

Breakthrough T1D has played a significant role in the evolution of AID systems. Doug Lowenstein, a long-time Breakthrough T1D volunteer and supporter, detailed the history of AID systems from the very beginning, and how we accelerated progress at every step of the way.

Discovery research

It’s the early 2000s. I’m a new AID system, but I don’t exist yet—I’m just an idea. I live in the minds of some scientists and researchers who think that I have the potential to one day become a reality. But, turning an idea into reality can be hard. It’ll take a lot of people, time, and effort for me to exist—but it’s not impossible. The question is: how? Answer: it starts with funding.

2005: Breakthrough T1D launches the Artificial Pancreas Project

Breakthrough T1D dedicates funds to scientists and researchers who have compelling ideas to turn AID systems into a reality, marking the start of the decades-long Artificial Pancreas Project (APP). These investments were key in jump-starting research into all the components needed to make an AID system work.

“[The goal was] to keep people alive and healthy until we find a cure. We were losing people…overnight of low blood sugars. If we could automatically dose insulin and have everybody go to sleep and all wake up, that was an incredible victory.” -John Brady, member of Breakthrough T1D Executive Committee in the early 2000s, former Chair of Breakthrough T1D’s International Board of Directors, and father of a son with T1D

Translational research

It’s 2008. Scientists are making progress on the three key parts that need to work in harmony for me to become a reality: a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), an insulin pump, and an algorithm that lets them talk to each other. But, like most new ideas, before I’m allowed to be tested on humans, I need to be tested in animal models first. Lucky for me, I skipped this step because someone made a tool that could simulate how I would act if I was attached to a human being.

2008: Breakthrough T1D-funded scientists create simulator tool to bypass animal studies

The simulator tool, developed from the initial Breakthrough T1D grants, allowed scientists to model how an AID system would respond to real-life scenarios, like eating a certain amount of carbs or exercising, and how this would translate to blood sugar outcomes like time in range or hypoglycemic events. The FDA accepting the use of this tool was a major win—without animal studies, AID system development was accelerated by years.

“The simulator saved at least five years of animal studies because we didn’t require an algorithm to be tested in an animal model to be deemed safe and effective before going into human studies. That entire chunk was eliminated.” -Sanjoy Dutta, Ph.D., Breakthrough T1D Chief Scientific Officer

Clinical trials

It’s 2012. Scientists have come up with different versions of my components that are ready to be tested in humans. For the next four years, I’ll be attached to people with T1D around the world who courageously volunteered themselves to test if I actually work. Turns out, I do a pretty good job at managing blood sugar—and I’m safe!

2012 to 2016: AID systems make headway in clinical trials

While clinical trials for AID systems started in earnest in 2008, they kicked into high gear in 2012, when investigators started conducting trials using different AID components and algorithms in real-life settings. Progress moved quickly, and results from numerous studies supported the idea that AID systems are both safe and effective. Breakthrough T1D funding—along with the Special Diabetes Program—helped move these trials forward.

“Getting involved in AID system trials to me was my chance to pay it forward for somebody else. I have lived 45 years with T1D…I think there’s something comforting in knowing that my body was used for something that not only had the potential to make me healthier, but really was for other people. I do think there’s something to be said for doing good, feeling good, and this is what it felt like being part of trials.” – Alecia Wesner

Regulatory approval

Flashback to 2009. While scientists are busy figuring me out, people at Breakthrough T1D are already thinking about and planning for my future—and how to work with the decision-makers at the FDA who will ultimately decide my fate. The FDA has also given their two cents about the best ways researchers can test me in clinical trials to get the data needed for me to get approved. Fast forward to 2016, it finally happens: I get FDA approval!

2009 to 2016: From APP roadmap to FDA approval

In 2009, Breakthrough T1D published the AP Roadmap, detailing what the future of AID systems will look like—and how we plan to get there. Two years later, we worked with the FDA on clinical trial design for AID systems so that there was a clear path to approval. After human clinical trials, the FDA approved Medtronic’s hybrid closed-loop MiniMed 670G—officially marking the first AID system to be available in the U.S.

“I do give [Breakthrough T1D] credit for pushing, for saying there’s a real need for this.” -Jeff Shuren, M.D., Head of the Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the FDA at the time

Access

Flashback to 2008. At this time, people were still unsure if one of my main components—a CGM—was a reliable way to measure blood sugar. This all changed when a first-of-its-kind clinical trial showed that CGMs are better than finger pricks and glucose meters, and they were covered by insurance shortly after. This decision paved the way for my future: after my approval in 2016, insurers began offering to cover me.

2008 to 2017: Insurance coverage evolves

The landmark Breakthrough T1D-funded clinical trial in 2008 provided the data to convince private insurers to cover CGMs. Nearly a decade later, Breakthrough T1D launched its “Coverage2Control” campaign to advocate for insurance coverage of T1D treatments, therapies, and devices—including AID systems—ultimately resulting in all major private insurers offering coverage of AID systems by the end of 2017, followed by Medicare shortly after.

“Seeing the artificial pancreas go from concept to reality…is what makes Breakthrough T1D and all of the advocacy volunteers—who sent an email, made a call, signed an action alert, or met with their Member of Congress—very proud of this historic achievement and the impact that these will have on the individual lives of those with type 1 diabetes.” -Cynthia Rice, former Chief Mission Strategy Officer at Breakthrough T1D

Adoption

It’s present day. There are tons of iterations of me, and even more coming. People get to choose which version of me they like best. I’m covered by most health insurance. I’ve come a long way since I was just another thought in the minds of a few scientists who had a vision… and now I’ve come to life! Even so, not everyone has chosen to use me yet—and I will continue to evolve and grow until I can make the lives easier of as many people with T1D as possible.

2017 and on: More and more AID systems come to life

After the first hybrid closed-loop AID system was approved, the flood gates were opened. More and more systems are coming to market each year, and they keep getting better. They’re smaller, easier to use, and better at managing blood sugar. They’re covered by both government and private insurance plans. They’re an integral part of routine discussions between people with T1D and their healthcare providers, and people have options to choose which system is best for them. This is a future that was difficult to imagine two decades ago—and now it’s a reality. Even so, the work continues until AID systems are a reality for more and more people with T1D.

“What we brought to bear is resulting in a safer and easier life for hundreds of thousands, and soon millions, of people with T1D, including my son, that is going to keep them safe until something like a cure comes along,” -Jeffrey Brewer, one of the APP founders

The final stage: Cures and improved lives

It took tons of time, money, people, and effort to get us where we are today, but we’re not at the finish line yet. “The end game for AID systems,” says Breakthrough T1D CEO Aaron Kowalski, Ph.D., “is to have multiple compatible pumps, glucose sensors, and algorithms, so that patients can mix and match what they prefer.”

The end game for T1D as a whole, however, is cures. AID systems have greatly improved the lives of those with T1D—and will continue to do so now and in the future—while we continuously work toward cures that are one day available to everyone with the condition.

The path followed for AID systems is a roadmap for other therapies coming down the pipeline. Breakthrough T1D’s Project ACT is taking a page from the AP roadmap and applying it to cell therapies, so that functional cures can get to people with T1D who want them as quickly and safely as possible.

While I’m proud of my work as a scientist at Breakthrough T1D on AID systems (and my brother and I currently wear AID systems that are derived from Breakthrough T1D-supported work), more than anything else I want to take off my diabetes devices and achieve what our founders set out to do—find cures for T1D.”

Breakthrough T1D successfully took an idea and turned it into a reality—and we’ll do it again and again until T1D is a thing of the past.